Archive for the ‘digital content’ Category

Both/And — or When You Come to a Fork in the Road, Take It

March 18th, 2015

Preamble (Don’t start the Prezi, linked to the image, just yet). I want to give just a little personal context, since it’s always good for people to know why you’re saying what you’re saying. Because I’m on LinkedIn, I had this weird experience as we hit 2015 – people wrote to congratulate me on the 15 years I’ve been overseeing Academic/Instructional Tech. That’s an insanely long time to be in a job like that, when you think of all that’s changed. But time does tell. (As Emerson said, the years teach much that the days never know.) Looking at reviews of recent publications — The End of College, for instance – I had this sense of déjà vu and went and pulled down The Social Life of Information (2000). Taking on the misguided prophecies of the nineties, it starts by saying that “the rise of the information age has brought about a good deal of ‘endism’” (16). So I want to say a little (more) to counter all the hype and hysteria about what technology will do to higher education as we know it, partly because we’ve been through this before.

OK. If you click on the image, you can follow along, advancing the presentation every time you see an underlined heading.

Revolutions/Game Changers – It seems lots of people talking about technology want to say that one thing or another is going result in a revolution or be a game changer. Such claims are so common we may fail to realize how rarely they’re true, Or maybe, which is at least as likely, we sense the terms themselves are abused and overused. Revolutions are dramatic changes — changes so dramatic they beg comparison to the violent overthrow of rulers by those they rule. Games, being highly rule-bound and regulated, change rarely because they necessarily change by a rewriting of the rules. Neither “revolution” nor “game-changer” seems to describe the changes that are essentially, at least according to Clayton Christensen, disruptions by outside forces or events or (especially) technologies. We are likely to get further with relevant examples and precedents than such fuzzy terms.

The Last Great Disruption – The past gives us a great point of comparison in the invention of the printing press and what ensued. It was both more and less radically transformative than it figures in the popular mind. We tend to forget that the ability to print books may actually be more easily and quickly effected than the widespread ability to read them — something, frankly, we are still working on. People at the advent of such changes are even less affected in seeing how they’ll play out. This is especially true of those who feel threatened by such change. They picture the consequences for themselves that may or may not come to pass.

The professors of the day were a case in point. They did feel threatened. They had access to texts, much fewer in number before than after the printing press intervened, and they imagined they would be less important or necessary because they saw their role largely as saying to their students what they texts said to them. As it turned out, saying what they books said was not the heart of teaching, or at least what teaching would become. That, instead, would lie in interpretations, applications, and extensions of understandings that would evolve over time, and widely accessible books, far from replacing teachers, would instead give them a starting point to do much more than say what was said.

Again, this took a long time. The real effect of the printing press on higher ed and the world at large required a vast growth in literacy and all the social and cultural and economic changes that would bring.

Not So Fast — So such changes are complicated, and one of the complications is surely that we can pretty much count on change being resisted. Opposing change has a long history, so much so that many posit it as an aspect of human nature. When Socrates spoke against writing in Plato’s Phaedrus (casting it as the enemy of memory), he was repeating arguments borrowed from the Egyptians, as far back in time to him as he is to us. This is not to say that Socrates was entirely wrong. In fact, he is the progenitor of the many moderns, people like Nicholas Carr and Sven Birkerts, who say that the Internet is the enemy of everything from sustained attention to careful thought. (By the way, if you want to read about faculty resistance to online education, I’ve blogged quite a bit about that, especially here.)

Sidesteps to Progress — It’s not just that technological innovations take time to overcome resistance and reach their potential. They are often not used as they were expected (even intended) to be used. The history of technology is a series of such stories. One example is how the epochal change in communication that telegraph amounted to and how all (from our perspective) equally epochal changes that followed — the radio, the telephone, the phonograph — were conceived of in terms of the initial guise of extensions of an invention they diverged radically from (and in some cases supplanted in the process).

Example of SMS – Again it’s not just the technology, but the use-niches it falls into and flows out of. To get a sense of all that is behind the reasons for texting, check out danah boyd’s It’s Complicated: the Social Lives of Networked Teens.

Both/And, not Either/Or – So we accommodate the new, arrange it on our landscape of options till the landscape itself is changed, and the (smart)phone leads to the erasure of the public phone. The point is that things do change, and dramatically, and faster than ever before because change has accelerated to the point that what has changed is change itself, becoming the expectation and the rule, not the disruption of that. I just mentioned the iPhone. It’s been with us less than a decade; we already can’t imagine life without being constantly accompanied by this thing that is our newsstand, entertainment center, library, game collection, camera — and, oh yes, phone. It’s not just public phone booths that have disappeared. What has happened to video stores, encyclopedias, half of our newspapers? If we take the long view in higher ed, how do we make the right bets?

Mr Rogers can help, ER and his Diffusion of Innovation, running through five editions and giving us the term “early adopter”, particularly his 5 attributes of innovations, and how they bear on our work – relative advantage (almost never cost initially, but the ability to do something better, is hard for educators to see, validate, and inculcate — because we don’t teach people how to teach in higher ed), compatibility (out-of-the-box doesn’t fit in our box), complexity (enough said), observability and trialability (a problem, teaching being oddly closeted).

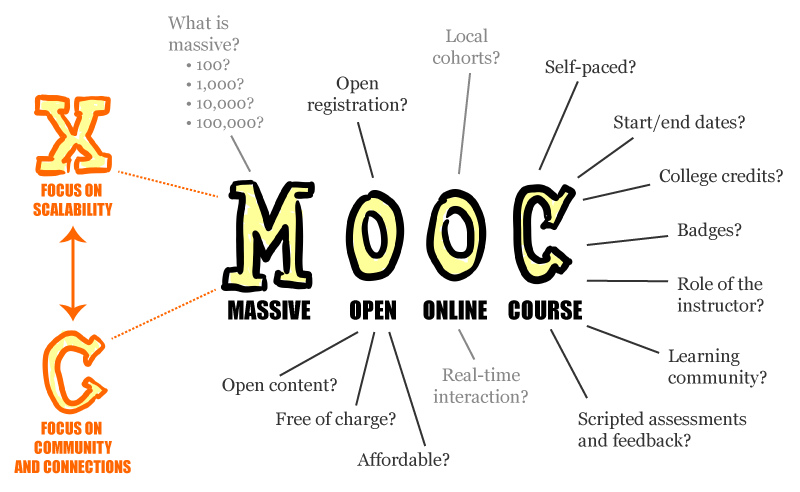

MOOCs amount to the exception that proved the rule — very observable and trialable (but that was part of the problem). The Massive Open Online Course was supposed to be the killer app for higher ed, our revolution and tsunami, but was a failure even (especially?) when free because at its heart it was the opposite of something new: a shopworn pedagogy, and an egregious scaling up of the large lecture class. Attempts to make it work turned out to be less massive, or open, or online, or even course-like – now absorbed into the landscape as a fringe element, useful for certain kinds of blending (the flipped MOOC), executive ed, and life-long learning. Note how, being old at heart, it was swallowed up by the already-there. Apparently we had to learn again what the printing press should have taught us half a millenium ago: transmission is not education.

So what will work? We need something that is essentially an update of Rogers, something that gives us a way to judge the value of technology in what educators value. Which brings us to

Zittrain’s 5 Aspects of Generativity – from his 2008 book The Future of the Internet—And How to Stop It. Generativity is Zittrain’s middle way between the twin dystopias of disruptive chaos on the one hand and corporatization or “appliancizing” (his word) on the other. The 5 aspects of generativity have a striking homology with Rogers’ 5 attributes of innovation: Leverage (cf. relative advantage – reach that is not so much scaling up as networking out, and moving from appointed time to point of need); Adaptibility (cf. compatibility – free from lockdown and compartmentalization); Ease of Mastery (cf. complexity — especially freedom from being led by the nose and told RTFM); Accessibility (cf. observability – free from the hierarchy of the top-down, getting in on the ground floor); Transferability (cf. triability – you cannot only try it out but make it your own, not just adopt it but adapt it). Want to see all this in action? Check out

The OpenLab : The best example of generativity I can think of. It’s a vast and vastly successful example of information made into knowledge and knowledge made visible. That was the whole point of The Social Life of Information: for information truly to inform (and not be inert data), for it to be transmuted into knowledge, it has to be socialized, applied through sharing and collaboration, built up mentoring and community building. That’s exactly what the City Tech’s OpenLab is and does, and it’s glorious.

One last slide: My contact info, in case you want to get back to me on any of this.

The Problem(s) with Innovation

May 12th, 2014

[This is my keynote at the Bronx EdTech Showcase on 5/9/14 — (reconstructed) text of the talk here,with access to the slides by clicking on the image. The upper-case headings are also slide titles — so, should you want to see the slides while reading the text, those headings will signal when to go to a new slide.]

[This is my keynote at the Bronx EdTech Showcase on 5/9/14 — (reconstructed) text of the talk here,with access to the slides by clicking on the image. The upper-case headings are also slide titles — so, should you want to see the slides while reading the text, those headings will signal when to go to a new slide.]

THE PROBLEM(S) OF INNOVATION

I feel I need to justify the title a bit. I’m coming to you with problems? What’s that about? First of all, since all you folks are innovators, let me say that you are not the problem(s). On the contrary.

But if I ask how many of you feel as noticed and supported and impactful as you’d like to be, you’re probably aware of something we might call the problematics of innovation. More on that directly.

Second, this is not just an exercise in problem definition. I do want to get on to some steps toward solution(s). But it is better to define a problem before trying to moving on to a solution

So the Problem(s) with Innovation can be traced to a larger institutional problem — the reasons innovation doesn’t take hold are also the reasons institutions are notoriously slow to change.

I won’t deny for a moment that we are talking about complicated dynamics (or lack thereof) , but I’m a great believer in simplifying (if not oversimplifying).

THE TENSIONS

So one way of looking at the problem(s) is to realize that we are dealing with a set of tensions — specifically, tensions between how innovation percolates up and how resources filter down.

Basically, we are talking about tensions between innovation being centrifugal and resource management being centripetal.

Innovation happens at the edges, is dispersed, scattered, disruptive because it happens outside of the established status quo.

Resource management is jtop-down: organized hierarchically, in clear chains of responsibility and control, subject to audits and so highly documented and monitored. (Anyone tried to get a purchase requisition through lately?)

Admittedly, there’s nothing epecially revelatory about seeing that ideas and money don’t flow the same way.

What’s worse, looking at it this way can induce apathy and even despair.

If we are going to think of what, if anything, we are going to do about this situation, we need to get to the bottom of these tensions.

THE QUESTION

WHO? WHAT? WHEN? WHERE? HOW? WHY?

The famous journalistic questions are supposed to help us analyze situations, but here I think they’ll just get us lost in the weeds. It’s time for simplification again. The key question is WHY? If these are differently motivated (as well as differently located) behaviors, what motivates them?

THE ANSWER

In a word, RISK.

- Innovation is all about taking risk. It’s being experimental, trying things out, testing hypotheses, being able to fail, revise, re-try.

- Effective resource management is risk avoidance. Resource management is essentially risk management.

The question is what happens when risk avoidance becomes risky.

THE MOMENT

It’s worth dwelling on the picture on this slide for a moment; it’s about Education, a bridge over Ignorance, and “Safety First” leads to the Road to Happiness.

Playing it safe might have been the Road to Happiness in 1914, but not in 2014.

The argument could be made that we have reached a game-changing moment when the most dangerous thing you can do is play it safe.

THE NEED

There’s an interesting analogy with not just what Steve Jobs said but what he was facing when, confronted with what seemed like insurmountable problems, he said ““The way we’re going to survive is to innovate our way out of this.” This was after he’d been kicked out of then brought back into Apple, post-bubble (and mid-recession, if not the Great Recession), with a sense that the excitement had gone out of technology while the pricy-ness and corporatization had escalated. In that crucible, we got Mac OS, the iPod and iTunes, the iPhone and iPad, IOS, and so on.

Jobs was not himself an innovator, of course, but he was a supremely effective driver, supporter, and vetter of innovations, roles that will be relevant to what I getting to.

In the meantime, think about where we are in higher ed: Funding from all levels is receding. A degree has never been important, but resources are ever leaner. Technology promises solutions but also higher costs and complications. Calls for reform abound as the challenges, especially stories of crushing student debt, raise concerns that institutions of higher education are unresponsive, inefficient, unable to change. Whatever else higher ed does, it can’t do nothing.

THE RESPONSE

That, of course, is part of the problem. Higher ed can be seen to be doing all sorts of things, but they are beginning to look like exercises in throwing stuff at the wall to see what sticks.

Dan Greenstein coined the term “Innovation Exhaustion” to describe the point this has brought us to, specifically with respect to MOOCs, which went through a huge hype cycle – talk of “campus tsunamis” and “revolutions” gave way to disappointing results and shrinking expectations. I don’t want to get off on a MOOC tangent, but the really significant thing about that explosion of hype and activity was that MOOCs, by definition, don’t need the mobilization of faculty: they are the printing press revolution of our time, a dramatic scaling of reach and access to content – like the lectures of a single professor (just as the printing press could widely disseminate the views of a single author). MOOCs function on the star system; you just need a celebrity prof and a platform or provider. In short, you can circumvent the system. Resource management can just fund some “hot” someone or something, doesn’t need to innovate or even foster innovation.

THE LAW

This is against the Law – or at least “Carlson’s Law” (Curtis Carlson being the head of SRI Int’l – one of those acronyms that doesn’t stand for anything, though it used to stand for Stanford Research Institute). This is what Carlson says about how innovation works — these days, at least:

In a world where so many people now have access to education and cheap tools of innovation, innovation that happens from the bottom up tends to be chaotic but smart. Innovation that happens from the top down tends to be orderly but dumb.

As a result the sweet spot for innovation today is “moving down,” closer to the people, not up, because all the people together are smarter than anyone alone and all the people now have the tools to invent and collaborate.

This is pretty interesting (and verifiable) when you think about it. Access not just to knowledge but to tools (not least of all the tools for tapping into “the wisdom of crowds”) ought to foster innovation, at least as long as we don’t have things getting in the way. The critical thing is figuring how far we should be “moving down.” (Quite a ways, perhaps, but how far is too far?)

THE (GOLDILOCKS) POINT – what’s not too high up, nor too low down

That’s not just a place – remember that we’re talking about not just the location but the motivation of behaviors.

So, let’s think about what we want from Innovation and Resource Management. [Two more mind maps.]

In both cases, we are thinking about two things – rights and benefits. (You could also call them expectations / goals & outcomes, especially if you’re doing Middle States work.)

Bottom line: Innovation needs Freedom and Flexibility; Resource Management (RM) needs Accountability and Evidence.

Above all, they need each other: Innovation is like a plant that needs watering; RM is like a watering can that has no reason for existing if it doesn’t support growth. They meet at Visibility: Innovation needs to get noticed; RM needs to notice what to support (if that watering can is not just going to soak the entire landscape — and remember that water here is a metaphor for money).

Steps in this direction

Let’s take ANOTHER LOOK AT CARLSON’S LAW, specifically what he says about the “sweet spot.”

Innovators have to notice each other, work together, realize that a rising tide lifts all their boats. They may be distributed out there at the fringes, but they need to find a way to find each other, work together, collaborate. So what are the ways?

THE CUNY ACADEMIC COMMONS

The CUNY Academic Commons is a great example of providing the means and the tools to invent and collaborate. It was itself built by collaboration. Memorably (I still get teased about it), I had told the team, “If you build it, they will fund” – and they did. By the time we got funding, a team had put together a beta version that had literally hundreds of people in it, banging away at it. I’m not sure that’s the model, but it is a model.

You’ll be hearing later, in the lightning panel, from members of one of the largest and most active groups on the Commons, the CUNY Games Network. If you think for a moment about the many skills sets entailed in educational gaming – you need design specialists, pedagogy people, programmers, and, yes, gamers – you realize that you have to tap into many fields and folks to get what you need. You pretty much have to work collaboratively. They do. The conference — the CUNY Games Festival — they put on in January was amazing.

Speaking of conferences, think how much collaboration this one represents, and how much use it made of the Commons platform.

I could go on, but I need to go on.

THE CUNY INNOVATION SURVEY — http://bit.ly/PUDqbB

This survey is the brainchild of another group on the Commons, the Innovative and Disruptive Technologies group. Realizing that supporting innovation, especially disruptive innovation, is probably not going to be a matter of telling the powers that be, “Give us money and we’ll do cool things,” the IDT group has accepted the challenge of documenting innovation that’s already out there and at work in CUNY, the better to build on that.

The trick is that this also requires collaboration. Enter the CUNY Innovation Survey. The approach taken is through self-reporting. We’ve reached a point in the survey responses where we have representation from all the campuses, and you can browse through the projects that way, but you can also view by category, type, and time of submission.

The point is giving the requisite visibility to what is going on — avoiding reinventing the wheel, failing to find synergies, but also learning from diversity (e.g., different approaches to eportfolio), and there are many things we can learn from each other.

In fact, one of our greatest resources in CUNY is each other. We are a multi-campus system that can and should learn from multiplicity, should share and diversify but also consolidate and reinforce effective practices and innovations.

Logical next steps (not yet taken because they have to be endorsed above my pay grade, and at this exquisitely transitional moment for CUNY, but there are encouraging signs that they may be):

- Structures for funding local innovations, start-ups, and plans. (I’m not speaking of external grants, which contribute to the ephemerality of innovations — the money stops flowing and the innovative practice dies or goes dormant; instead, I’m speaking of opportunities for CUNY to invest in its innovators — and invest further if successful innovation seems worth scaling up.)

- Structures for developing springboards for collaboration: participatory MOOCs and workshops and roundtables or seminars that ready faculty to learn more, get to the next level.

- Opportunities for mentoring – both to do it and to have it done unto you, and in environments where everyone has the time to do this.

I’ll leave you with means of contacting me, and how better than through MY CUNY PROFILE, a major feature of a major upgrade of the Commons. What you’re seeing is just the top: you can also find my bio there, my publications, my interests, my positions (more than you want to know, really). It’s something everyone should use, particularly for a point of connection I’ll draw your attention to – the CUNY.IS/your-name-here URL shortener. This is not an act of hubris but an acknowledgement that, like the hundreds who use the same kind of CUNY.IS/_____ quick link (may there soon be thousands) we are all CUNY: together, collaboratively, we are what CUNY is.

That’s one the thought I’d like to leave you with, that and

Innovation is not tech; Innovation is people.

The solution is not a hierarchy; the solution is a network.

MOOCs: Flame out or Flame on?

March 28th, 2014

Be careful what you wish for. Started back in 2009, this blog on academic technologies was hijacked in 2012 (“the Year of the MOOC“) by MOOCs. I felt so compelled to blog about these hyper-hyped (then much transmogrified) Massive Open Online Courses (getting less massive, less open, less fully online, and less course-like all the time) that, after one or two retrospectives, I’m sort of at a loss when it comes to what to blog about these days, now that the once mighty MOOC zeppelin seems a deflated blimp. Not that I couldn’t find plenty to say about ed tech and online learning and so on BM (Before MOOCs). So I’ve decided to do a combination update/valedictory and move on. At least for the nonce.

Be careful what you wish for. Started back in 2009, this blog on academic technologies was hijacked in 2012 (“the Year of the MOOC“) by MOOCs. I felt so compelled to blog about these hyper-hyped (then much transmogrified) Massive Open Online Courses (getting less massive, less open, less fully online, and less course-like all the time) that, after one or two retrospectives, I’m sort of at a loss when it comes to what to blog about these days, now that the once mighty MOOC zeppelin seems a deflated blimp. Not that I couldn’t find plenty to say about ed tech and online learning and so on BM (Before MOOCs). So I’ve decided to do a combination update/valedictory and move on. At least for the nonce.

There are two forks to the waning stream of stories on MOOCs. One still rings positive. The other, the dominant, is that they’re so over. Far from being the tsunamis or revolutions that would wash away or remake higher ed as we know it, they’re at best a part of the “incremental change” that higher ed is seeing from technological and putatively disruptive incursions, or so says “The Sky Isn’t Falling,” a report on SXSWedu, “which featured cautious and intentional ways of trying out emerging technologies” and came to the general conclusion that “ed tech will continue to be used as a complement to traditional higher education.”

And this is what the advocates are saying. Meanwhile, some highly placed people are raining on the parade already past. Hillary Clinton, speaking at the Globalization of Higher Education conference earlier this week in Dallas, did not criticize MOOCs and online learning specifically, but she did (as cited in Inside Higher Ed) say there’s “no substitute for the kind of learning that takes place in a well-taught classroom,” and that “technology is a tool, not a teacher.” And former fellow Cabinet member, now UC President Janet Napolitano, “joins skeptics over online courses” (as Monday’s Reuter headline had it), specifically those big productions that are supposed to handle more students at a lower cost: “There’s a developing consensus that online learning is a tool for the toolbox, but it’s harder than it looks and if you do it right, it doesn’t save all that much money,” she said about the prospect of cheap online courses that might let California educate more students for less money.

From 30,000 feet, it may be hard to tell the kind of online courses we have been doing for the past two decades from the MOOCs of the past two years, but academic administrators, a little closer to the ground, have no such trouble. In the 11th annual report tracking online education in the US, it turns out that, in the space of just the past year, the number of academic leaders who thought MOOCs were sustainable online offerings dropped 5% (from 28% to 23%), and the number who had concerns about credits or credentials from MOOCs went up almost 10% (from 55% to 64%). (By contrast, the number reporting that online education generally — not just MOOCs — was not critical to their institutions’ long term strategy dropped to an all-time low, below 10%.)

So are MOOCs just a blip? Given not just the attention but the investment afforded MOOCs, you would expect some resilience to them. But where will they flow, like water blocked in one channel but not another? Some sense of an answer may be in the very critiques and declarations of failure. The low completion rates are notorious, even in the popular press, and not least of all in the Times, which fed so much of the original hoopla with pundits like Brooks and Friedman and big spreads like the one on “the Year of the MOOC“; but in another sense the limits of their wide reach was a sign that being big didn’t mean reaching (and especially working for) everyone. As the potential retracted, it essentially redefined the logical market: the successful students for MOOCs were those who were already college educated, and this was especially true of MOOCs that had that touted global reach.

Enter the latest news: Coursera has hired Richard C. Levine as its new CEO, and edX has Wendy Cebula as its new president and COO. Levine was the president of Yale, while Cebula was a Vistaprint executive (and it’s interesting that the open source provider should be the one to go with the corporate figure). But what they have in common, besides the intriguing synchronicity of these announcements, is expertise in reaching beyond standard market definitions. Levine is an acknowledged leader in the internationalization of higher ed; Cebula is an expert in “global growth.” You can expect both of the remaining big three MOOC providers (now that Udacity has left higher ed for corporate e-learning) to go after the market for higher ed abroad that fits their strengths: the hungry but not the starving, the eager-to-be-elite. (There’s more to the reconfiguration of the major MOOC providers than these recent appointments signals, but I noted as much in an earlier post.)

So MOOCs will fill the interstices, and not the ones that most need filling. But we shouldn’t confuse the evolving business model with the lessons MOOCs have taught: that teaching (and its reach) can scale dramatically, that new modes and media make for new possibilities, that what might not succeed as a standalone may work well and complement or supplement. Cathy Davidson’s recent MOOC (to a considerable extent a MOOC on MOOCs) pulled out all the stops to show what a rich trove of possibilities that is, with layered readings, guest lectures, local as well as online discussion groups, multiple tiers of participation and evaluation. Even in this form (or array of forms), and pace Clinton and Napolitano, online learning is not just a (singular) technology or just a (singular) tool but a huge bag of tricks we’ve only begun to learn how to play with.

The Story of MOOCs (Chapter 3.14…)

October 15th, 2013

The story of MOOCs is not a single story. Once touted as higher ed’s own singularity, there’s nothing singular about MOOCs any more. They come in all sorts of shapes and sizes, openness and course-ness. And the point that they’re all over the place (in all senses) has been made ad infinitum. So why do we feel like we’re going around in circles about whether they’re a good thing or a bad thing (as if they were one thing)?

Some of this is the familiar pattern of action and reaction, so regular it has begun to feel like the tick tock of a pendulum. My last blog post — “Skepticism Abounds” — took its title from a report on a survey of faculty and administrators regarding online learning generally and MOOCs in particular. The same day, in the same source for that report (Inside Higher Ed), came a piece from the president of the American Council on Education (ACE) meant to be reassuring. Titled “Beyond the Skepticism,” it noted that there were indeed reasons to be skeptical, that “it hasn’t taken long in many quarters of our community for acclaim to accede to skepticism, and excitement about MOOCs to fade amid charges of excessive hype.” But not to worry: ACE will vet these MOOCs and decide which are worthy of credit. No sense here that faculty might be skeptical about that independent vetting — certainly independent of said faculty.

But the naysayers have their own organizations, and now they’ve gone “meta”– combining no fewer than 65 organizations into one coalition. No longer limiting their protests to a vote here (from the Rutgers faculty) and a letter there (from the San Jose State faculty), they have the Campaign for the Future of Higher Education. Its first report, subtitled simply “Profit,” warns against the entrepreneurial aspect of MOOCs and online learning, which got the attention of the Chronicle of Higher Ed, Campus Technology, and Inside Higher Ed. According to that last, “The report ties the current state of higher education to industries that have recently experienced economic downturns. The unregulated growth of ed-tech companies is described as a boom-and-bust cycle similar to the dot-com bubble that burst in the early 2000s, while rising student loan debt burdens and default rates are compared to the factors that led to the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis.”

That’s painting with a broad brush, but that’s done equally artfully by both sides. A defender of MOOCs, James G. Mazoue, promises to explode the “myths” about MOOCs in the latest EDUCAUSE Review, but as a counter-argument it’s really my-straw-man-meets-your-straw-man. The “myths,” framed as statements like “It’s All About Money” or “MOOCs Are Inherently Inferior,” are phrased as the kind of absolutes we’d know to mark False on a True-False test even if we knew nothing about the subject. Of course there exceptions to those statements, we think. In fact the real problem is that most MOOCs are themselves exceptions, one-offs and stand-alones, not curricula or integrated parts of a larger plan. Go ahead, just try to generalize about them. Or even try to frame expectations about them. Wait… Could that be a problem? Could that, right now, be the problem?

Problems or not, MOOCs were for so long (or at least loudly) framed as a solution, and there it really is all about money, even and especially if the O-for-open means both accessible and free. The problem is that higher ed currently works on an increasingly expensive and possibly unsustainable business model, especially in these days of shrinking public support. This is something William G. Bowen treats with remarkable candor in “The Potential for Online Learning: Promises and Pitfalls,” which appears in the same EDUCAUSE Review as Mazoue’s myth-busting article. What Bowen has to say on the subject is quite bracing — and worth quoting at length:

Faculty members understandably fear job losses, as Professor Albert J. Sumell, at Youngstown State University, cogently and sympathetically explains in an article aptly titled “I Don’t Want to Be Mooc’d.” Although there are ways of minimizing such risks of job loss (e.g., by redeploying faculty to higher-value tasks and by teaching more students), we have to be prepared to contemplate shifts in faculty ranks—both in overall numbers and in composition. We also have to recognize the implications of such possible changes for graduate education and for what is called “departmental research.” John Hennessy, at Stanford University, is one of the few leaders in higher education willing to be brutally candid in talking about such subjects.

The plain fact is that a combination of fiscal and political realities will continue to put inexorable pressure on the economic structure of higher education in the United States, especially in the public sector. Although an intelligent reexamination of tuition policies and financial aid policies can be of some help, I do not think there is any way to avoid thoroughgoing efforts to raise productivity—both by reducing the “inputs” denominator of the productivity ratio and by raising the “outputs” numerator.

Bowen really does explain something here: why the discussion of MOOCs and alternative modes is getting such attention — not least of all from administrators — even without solid successes or a proven business model. (Speaking of sustainability, giving it away is not a long-term option either, as everyone knows.) Costs are exceeding the power of institutions to control or students to bear. Change is already happening, in other words, and it is carrying away treasured ideas of equity and mobility. As the New York Times pointed out earlier this year, important studies are documenting the extent to which the educational gaps between the rich and poor are worsening, widening. MOOCs, especially in their current state — where so often the “sage on the stage” just becomes the “doc on the laptop,” as Cathy Davidson puts it — aren’t yet a fix, much less a cure-all. But they might be a crack in the wall. And the choice is not the false dichotomy between accepting or resisting change; the best choice, the third path, might be resolving to give it the right direction.

Heal Thyself

January 23rd, 2013

I was struck by a recent blog post by Cathy Davidson (of Duke U and HASTAC), and not just because it opens with this slide, the one she opens all her presentations with here lately. “That gets people’s attention,” she says. I’ll bet.

I was struck by a recent blog post by Cathy Davidson (of Duke U and HASTAC), and not just because it opens with this slide, the one she opens all her presentations with here lately. “That gets people’s attention,” she says. I’ll bet.

But what has to be at least as attention-getting is the title of her blog post: “If We Profs Don’t Reform Higher Ed, We’ll Be Re-Formed (and we won’t like it).” That, too, is bracing, but is it really up to profs to reform higher ed? That’s a question worth asking, since the problems Davidson lists are pretty formidable: that college educations are highly desirable but hard to get into, hard to pay for, hard to complete. This has lots of venturesome ventures and for-profits lining up to say their feet will fit the glass slipper, but how realistic is that really?

Something similar is happening in a recent “manifesto” released by (or at least under the auspices) of the American Council on Education. The manifesto (full title: “Post-traditional Learners and the Transformation of Postsecondary Education: A Manifesto for College Leaders”) concludes by calling for “a bottom-up entrepreneurship” that occurs from within. Too many distractions (disruptions?) are being brought to bear from without, or so says a recent article in Inside Higher Ed on the manifesto and its author, Louis Soares: “Much of the conversation about innovation in higher education is occurring outside of the academy, Soares said. He would like to see that change.”

That sentiment is not hard to share, no more than the author’s conviction that “post-traditional” (read “adult”) learners represent a great (and largely) unfulfilled need on higher ed’s agenda. What may be a little harder to affirm is the ability of college leaders to re-set their agenda thus — or re-set it period. That may even be behind the way, according to the IHE article, “ACE issued a disclaimer with the report, noting that it reflects the views of Soares, and necessarily those of the council.”

There’s a certain tilting-at-windmills angle to these calls for higher ed faculty or administrators to fix the problems confront them. These are problems of cost and economy, shifting demographics, cultural change and value — things “outside of the academy.” To be sure, there are plenty of calls for change — and responses to them — coming from outside as well. So many, in fact, that if change is conceived as some sort of single (unitary if monolithic) construct, it also seems a juggernaut, creating that feeling that you either get on board or get run over.

This is not to say that standing still or sitting on your hands is a good idea. It’s not even an option. But when exhortations seem to suggest there’s one right way to go — and you need to head off in it — there’s a wonderful curative. You just need to think about how all-over-the-place current attempts at reforming or reinventing college seem to be. A moment that crystallized this for me was when a high-level CUNY administrator listened patiently to the description of what a MOOC (Massive Open Online Course) was (with a nod to retention problems, shuffles toward credit and credentialing [and monetizing all that], far-flung demographics, etc.). “If that’s a solution,” he asked, “what problems does it solve for us?” Good question.

An answer of sorts is the latest update in who’s jumping on the MOOC bandwagon. “Public Universities to Offer Free Online Classes for Credit,” The New York Times reports, though the new wrinkle is really that a commercial venture, Academic Partnerships, will recruit students for the free course for a share of the tuition they pay if they continue with the degree. Described as “a bold strategy” in the Times article, this try-then-buy ploy, with a commercial partner brokering that, is transparently more about marketing than pedagogy. Innovation as bait: doesn’t this return us to Davidson’s slide and the questions she provokes with it?

Money from MOOCs

November 29th, 2012

A colleague sent me a very interesting article. (Thanks, Bruce.) “Coursera will profit from ‘Free’ courses” its title declares. That’s not entirely new news. I noted some time ago that a freedom of information request had made the Coursera contract an open book, complete with 8 (count ’em, 8) ways of monetizing its Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs). But this piece, actually linking to the contract, enumerates and describes the ways, and speculates on more ways to make money from MOOCs with other, better(?) business models.

A colleague sent me a very interesting article. (Thanks, Bruce.) “Coursera will profit from ‘Free’ courses” its title declares. That’s not entirely new news. I noted some time ago that a freedom of information request had made the Coursera contract an open book, complete with 8 (count ’em, 8) ways of monetizing its Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs). But this piece, actually linking to the contract, enumerates and describes the ways, and speculates on more ways to make money from MOOCs with other, better(?) business models.

The discussion includes news that commercial learning management systems like Blackboard and Desire2Learn are jumping on the MOOC bandwagon. The idea, suggests the article (drawing on thinking about possible business models gathered at quora.com), is that the MOOCs from these commercial providers would function as loss-leaders or teasers — a taste of online instruction that would make users/learners want more (and pay for it).

None of this is surprising. With Coursera investing $22 million in venture capital (and it has been around less than a year), it is going to want to make that money back sooner or later — and sooner rather than later. It could do that through corporate sponsorship, certifications, partnerships (like its rival edX has already forged with the UT system), and so on.

One particularly compelling business model outlined in the article is the “freemium-to-premium” approach:

Freemium – Where you split the learning options along the lines of Bloom’s Taxonomy and make free those courses that target “Knowledge & Understanding” learning outcomes but charge a premium for those follow-on courses that target higher cognitive skills like “Applying, Analyzing, Synthesizing, Evaluating and Creating”.

What’s especially compelling about this is that, if you know your Bloom’s Taxonomy, the split between remembering (at the bottom) and analyzing, evaluating, and creating (at the top) is actually a spectrum, ideally a continuum, and you shouldn’t put walls — especially paywalls — between the learning objectives/opportunities.

Another configuration, designed less with profits and more with pedagogy in mind, would be a grand and glorious variant on the flipped classroom, where the instructional content is contained (and consumed) in something MOOC-like, but the critical inquiry and individualized, point-of-need instruction happens in a cozier, more interactive, and (yes) more traditional classroom environment. I’m not sure how you’d wring profits from such an arrangement, but I think we all can see how it could help make effective learning happen. And isn’t that the real point of courses, however massive or open or profitable?

Degrees of Openness?

November 12th, 2012

At the EDUCAUSE conference in Denver last week, Clay Shirky did the big keynote. Though you wouldn’t know it from its title (“IT as a Core Academic Competence”), it was all about openness. The coverage given it in the Chroncile‘s blog — “The Real Revolution Is Openness, Clay Shirky Tells Tech Leaders” — makes that pretty clear.

At the EDUCAUSE conference in Denver last week, Clay Shirky did the big keynote. Though you wouldn’t know it from its title (“IT as a Core Academic Competence”), it was all about openness. The coverage given it in the Chroncile‘s blog — “The Real Revolution Is Openness, Clay Shirky Tells Tech Leaders” — makes that pretty clear.

What is less clear these days is what we mean by openness. And that’s increasingly important. An odd indication of that was a display in the middle of the registration area at the conference: a rectangular mat of astroturf was marked “The IT Landscape” and three “real estate” signs planted in it read “MOOCs” and “Openness” and “Analytics.” (Whoa, I thought. Just three things? Was someone stealing the signs?)

Whether there are other prominent trends, I think we all recognize not just the importance of these, but their complexity, the ambiguity and ambivalence around them. It’s not hard to see that “analytics” — use-tracking, data-crunching, and the like — is rich and vareigated, and the recent NY Times piece on MOOCs (see my blog entry last week) stresses a growing sense that MOOCs come in vastly different sizes, flavors, and valences. But isn’t open, well, an open-or-shut deal?

No. In a consumer culture that taught us all, at a very early age, that “free” almost always meant “strings attached,” we’re finding that open doesn’t always mean wholly open. This varies according to what we put the word “open” in front of — words like “access” and “standards” and “source” — but we shouldn’t get lost in the weeds. Some restrictions on just how open things are matter more than others, because some things are matters of flow and principle.

A big one — it was certainly big in Shirky’s keynote — is not just what “open” means you have access to but what you can do with it. For some people (I count myself one), the idea that you are on the ‘net not just to look but to do is key, the Web 2.0 difference, the difference between passive consumption and creative re-production. In what Lessing has taught us to call a “remix” culture, the ability to use what we find and even repurpose it is critical.

Which is why one response to Shirky’s keynote — an article appearing the day after in Inside Higher Ed— is worth noting. In “How ‘Open’ Are MOOCs?” author Steve Kolowich reports Shirky as saying that “the most provocative aspect of MOOCs is not their massiveness; it is their openness.” “Or their lack thereof, ” continues Kolowich, and then goes on to cite the terms of service from the big MOOC providers: edX ‘s statement that “All rights in the Site and its content, if not expressly granted, are reserved”; Coursera’s restriction that, beyond personal and informal use, users may not “copy, reproduce, retransmit, distribute, publish, commercially exploit or otherwise transfer any material, nor may you modify or create derivatives [sic] works of the material”; Udacity’s similarly worded prohibition that its users “may not copy, sell, display, reproduce, publish, modify, create derivative works from, transfer, distribute or otherwise commercially exploit in any manner the Class Sites, Online Courses, or any Content.”

This is not the point to get all huffy and suggest that these entities, having invested so heavily in their free (but only to a point) offerings, have no right to say as much. Openness is more a spectrum than a state, and I find one of my earliest entries on this blog, over three years ago, was a meditation on how open the CUNY Academic Commons should be. (The consensus-determined answer can be had with a quick scroll to the bottom of this or any page on the Commons: the default is licensing under Creative Commons; just which license can be confirmed with a click.)

What makes the restrictive terms of service from the major MOOC providers a real issue may be their role, less as massive open online courses, than as conspicuous (“massive”) elements in the universe of open educational resources (OERs). Here, it seems, they are not on the most open end of the open-ended spectrum, restricting not just the use of materials but also the capacity of their courses to count for anything. “You may not take any Online Course offered by Coursera,” Kolowich quotes from that company’s terms of service, “or use any Letter of Completion as part of any tuition-based or for-credit certification or program for any college, university, or other academic institution without the express written permission from Coursera” — this to explain why Antioch University had to enter into a contract with Coursera to count any of its courses for credit.

Again, the issue is not whether Coursera had a right to do what it did when it “drew a line on the extent to which the company would allow outsiders to use its resources without paying to do so” (as Kolowich puts it). The issue is whether we are all fully aware of how not-so-open are some massive open online courses whose openness is declared in their label and encoded in their acronym. And this seems especially consequential in light of a survey Kolowich reports on but doesn’t actually mention by name: Growing the Curriculum: Open Education Resources in U.S. Higher Education (November 2012). The survey shows that 65% of the chief academic officers surveyed thought OER could save money for their institutions, but when Kolowich asked Jeff Seaman, one of the survey authors, if any were aware of licensing issues or any restrictions on openness, his response was telling: “‘Not mentioned,’ said Seaman. ‘Not on the mindset at all of these chief academic officers. The idea of who did it, how I can use it, what the permissions are for use, can I re-purpose it — never appeared in any of the examples that they described.'”

Hmm.

MOOCs Redux

November 5th, 2012

The Education Supplement of the New York Times this Sunday had a long feature article on “The Year of the MOOC.” The supplement cover has an albino rabbit, its pink eyes framed by the Os in MOOC, staring out at the reader — the implication being that these MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses) are multiplying like rabbits. Point taken. Anyone who has ever had an albino rabbit, however, knows the lack of pigment in its eyes can cause poor eyesight and vision problems, problems not unlike some noted in the article.

The Education Supplement of the New York Times this Sunday had a long feature article on “The Year of the MOOC.” The supplement cover has an albino rabbit, its pink eyes framed by the Os in MOOC, staring out at the reader — the implication being that these MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses) are multiplying like rabbits. Point taken. Anyone who has ever had an albino rabbit, however, knows the lack of pigment in its eyes can cause poor eyesight and vision problems, problems not unlike some noted in the article.

The medium is still the lecture…. Feedback is electronic. Teaching assistants may monitor discussion boards. There may be homework and a final exam.

The MOOC certainly presents challenges. Can learning be scaled up this much? Grading is imperfect, especially for nontechnical subjects. Cheating is a reality. “We found groups of 20 people in a course submitting identical homework,” says David Patterson, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, who teaches software engineering, in a tone of disbelief at such blatant copying; Udacity and edX now offer proctored exams.

Some students are also ill prepared for the university-level work. And few stick with it.

All that said (and I had noted such problems in one or two or three or four earlier posts), the sense of excitement is palpable. Laura Pappano, the author of the article, incarnates it in Nick McKeown, one of a pair doing a Stanford-based MOOC on computer networking: “Dr. McKeown sums up the energy of this grand experiment when he gushes, ‘We’re both very excited.’ Casually draped over auditorium seats, the professors also acknowledge that they are not exactly sure how this MOOC stuff works. “We are just going to see how this goes over the next few weeks,’ says Dr. McKeown.”

There’s nothing wrong with feeling our way. In fact, one of the refreshing things about this overview is the way it captures the frontier spirit and ad hoc mash-up that is the current state of MOOC-dom with headings like “WHAT IS A MOOC ANYWAY?” and “WORKING OUT THE KINKS.” Increasingly, MOOCs come in different styles and “flavors” (a word taken from one of the other headings), something a lead graphic tries to capture:

Clockwise, from top left: an online course in circuits and electronics with an M.I.T. professor (edX); statistics, Stanford (Udacity); machine learning, Stanford (Coursera); organic chemistry, University of Illinois, Urbana (Coursera).

Also, a sidebar not available online but only in the paper supplement presents a comparison chart of how the major players among the MOOC offerers (“The Big Three”: edX, Udacity, and Coursera) differ by such critical considerations as assessment, academic integrity, and social interaction. In fact, one of the points of the article is the growing need to discriminate among MOOCs in terms of their “flavor” and quality. Duke prof Cathy N. Davidson is quoted as saying, “We need a MOOCE — massive open online course evaluation.”

I said in an earlier post that it would be a wrong to mistake MOOCs with online learning generally. As important as it is not to generalize from MOOCs to all of online learning, it’s be increasingly important not to generalize MOOCs as a uniform category, mistaking one for another as if they were like, well, so many white rabbits. We’ll see better practices emerge, better breeds, interesting mutations. Here is an area where the hype is actually outpaced by the changes wrought almost daily, an area to keep an eye on.

An “IR” of Our Own

October 29th, 2012

The culmination of Open Access Week at CUNY was a series of presentations at the CUNY Grad Center on Friday the 26th. And while it’s wrong to settle on one day in a whole week of events, still more wrong to highlight just one presentation among many, I’m going to do it anyway. Jill Cirasella of Brooklyn College (and of the UFS Open Access Advisory Group) gave a presentation that explained “Why We Need an Institutional Repository.” That explanation (available with a click on the afore-offered hyperlink) is 36 slides of compelling information and argument everyone should take the time to go through. But let me highlight a few of the main points here.

The culmination of Open Access Week at CUNY was a series of presentations at the CUNY Grad Center on Friday the 26th. And while it’s wrong to settle on one day in a whole week of events, still more wrong to highlight just one presentation among many, I’m going to do it anyway. Jill Cirasella of Brooklyn College (and of the UFS Open Access Advisory Group) gave a presentation that explained “Why We Need an Institutional Repository.” That explanation (available with a click on the afore-offered hyperlink) is 36 slides of compelling information and argument everyone should take the time to go through. But let me highlight a few of the main points here.

As Jill notes, one of the reasons we need an Institutional Repository (IR) is because we said we do. The University Faculty Senate passed a resolution in support of “”the development of an open-access institutional repository for the City University of New York” in November of last year, and the full text of that resolution is available in a report posted by (guess who?) Jill Cirasella.

The reasons for having an open-access IR (like the resolution’s whereases) are many, and they include the observation that most universities (especially universities anywhere near the size of CUNY) have them. But this is more, much more, than a matter of keeping up with the Joneses.

As Jill’s presentation makes compellingly clear, there are may potential benefits to CUNY, including raising its profile and strengthening its reputation, and doing so not just in the academic world but in the wider public realm. That would of course be away of doing the same for its faculty, but it would also make their collaboration easier and more productive, even as it would make it much easier for them to share materials with students, who would in turn be spared textbook costs while improving their information literacy. Libraries as well as students would save money by purchasing less of what doesn’t get used while having more (open) access to what does.

In fact, there are so many reasons to do have an IR (reasons which should be considered with Jill’s fuller treatment of them, complete with graphs of expenditures and quotations from reports) that the only real question might also be the obvious head-scratcher here: why haven’t we set one up already? The short answer: we want to do this right. This isn’t the first or second time I’ve talked about an IR for CUNY in the last few months, and the one thing I keep returning to is the other no-brainer besides doing it: doing it differently. Too often IRs are static dumping grounds or the digital equivalent of vanity presses. We have an opportunity to learn from what has been done — and to do better. One great chance for us is to modify the essentially static nature of the Institutional Repository (the name itself signals something staid and inert) by tying it to the dynamism of the CUNY Academic Commons.

The Commons is itself an example of what we need to do. It was not the first of its kind, but it was so clearly the most innovative that it has become an award– and grant-winning exemplar, now completing a plan to make its ways of working more available to others. Its Commons In A Box project has institutions lining up for their “box,” from other schools to a huge professional organization like the Modern Language Association. We can, at least potentially, have a similar effect on the world of IRs, islands on information too often unvisited. We have the means to network ours with our constituencies’ needs and interests. But we do need to get started.

Divining Madness

October 2nd, 2012

The annual “special section” on online learning done by the Chronicle of Higher Education is out, and it’s (almost) all about MOOCs. The cover proclaims “MOOC Madness,” and the big article is “MOOC Mania.” How apt. I used that same title a couple of months ago in voicing my skepticism about all the hype , and have had cause to return to that theme again and again. Now the validation given to this fringe phenomenon by the popular press makes me feel, if only for a paranoid moment, like a voice crying in the wilderness. MOOCs have not only arrived; the juggernaut has rolled past — crushing any naysayer in its wake.

The annual “special section” on online learning done by the Chronicle of Higher Education is out, and it’s (almost) all about MOOCs. The cover proclaims “MOOC Madness,” and the big article is “MOOC Mania.” How apt. I used that same title a couple of months ago in voicing my skepticism about all the hype , and have had cause to return to that theme again and again. Now the validation given to this fringe phenomenon by the popular press makes me feel, if only for a paranoid moment, like a voice crying in the wilderness. MOOCs have not only arrived; the juggernaut has rolled past — crushing any naysayer in its wake.

But wait a minute. What the articles actually reveal is something less than a wholehearted embrace. I was naturally first drawn to Ann Kirschner’s sampling of a MOOC (something I’m doing as well). The Dean of CUNY’s Macaulay Honors College is in many ways the ideal student, trying something she actually envisioned years ago while forging Columbia’s Fathom. She’s already knowledgeable about the subject, pressed for time, yet genuinely interested, ripe to find the MOOC she tried a useful learning resource. But it’s far from an ideal learning environment, and she’s quick to point what’s missing: “There was no way to build a discussion, no equivalent to the hush that comes over the classroom when the smart kid raises his or her hand.”

Other authors are harder on the next big — and we do mean big — thing. Much, both positive and negative, has been made of Sebastian Thrun’s famous MOOC on Artificial Intelligence, which initially enrolled 160,000 students but saw only 20,000 complete it. Greg Graham, a writing instructor, doesn’t even mention the completion rate. He’s horrified by the sheer number enrolled.

Perhaps Thrun and others like him have made the classic mistake of valuing quantity over quality. Those huge numbers on their screens are clouding their judgment about what is wrong with our education system and what it will take to fix it. Like Wal-Mart, online education promises greater numbers: To hell with customer service and quality; we’ve got discounts!

This seems a little shrill, but it does, from another angle, explain the lure of MOOCs. Those sheer numbers seem an answer to the cost disease presumably afflicting faculty productivity. If we employ conventional methods, there’s no way, with the cost of everything (including faculty) going up, that we can produce more educational “product” more cheaply. So it’s easy to imagine the administrator’s version of Thrun’s now famous comment, “You can take the blue pill and go back to your classroom and lecture to your 20 students, but I’ve taken the red pill and I’ve seen Wonderland.” Wonderland, indeed. If you’re an university president, imagine the thrill of getting so much more out of that first-rate prof you’re paying that six-fiigure salary to by getting six-figure enrollments.

Dean Kirschner is right: “Let’s give this explosion of pent-up innovation in higher education a chance to mature before we rush to the bottom line.” Yet there is another kind of rush on, and of a very different kind. Last Friday the Wall Street Journal published a piece on “educational competitiveness” rankings that showed how investments in Asia were changing the global higher ed landscape — pushing China above Germany, for instance, and just below the US and the UK. China now has its own analog of the Ivy League — the C9 — and its formula for success is not that much different from that of the Ivies — maximum investment (in faculty) and maximum selection (of students).

Whether MOOCs are a giant step forward, this seems a giant step backward. Surely there has to be something between this resurgence of social Darwinism and the assembly-line anonymity of some MOOCs. Technology can be about intimacy as well as reach, and reach can take into account need, not just ability or merit. We don’t need to decide whether to accept or reject MOOCs — that’s premature. But we do need to decide how to modulate as well as realize the possibilities they represent, particularly so they can reach the kinds of students CUNY is committed to.